How I Built the Most Accurate Memory System in the World in 5 Days

I built a memory system in five days that beat every published result on the most widely used long-term memory benchmark in conversational AI. It has no vector database, no knowledge graph, no embedding model, and no retrieval pipeline.

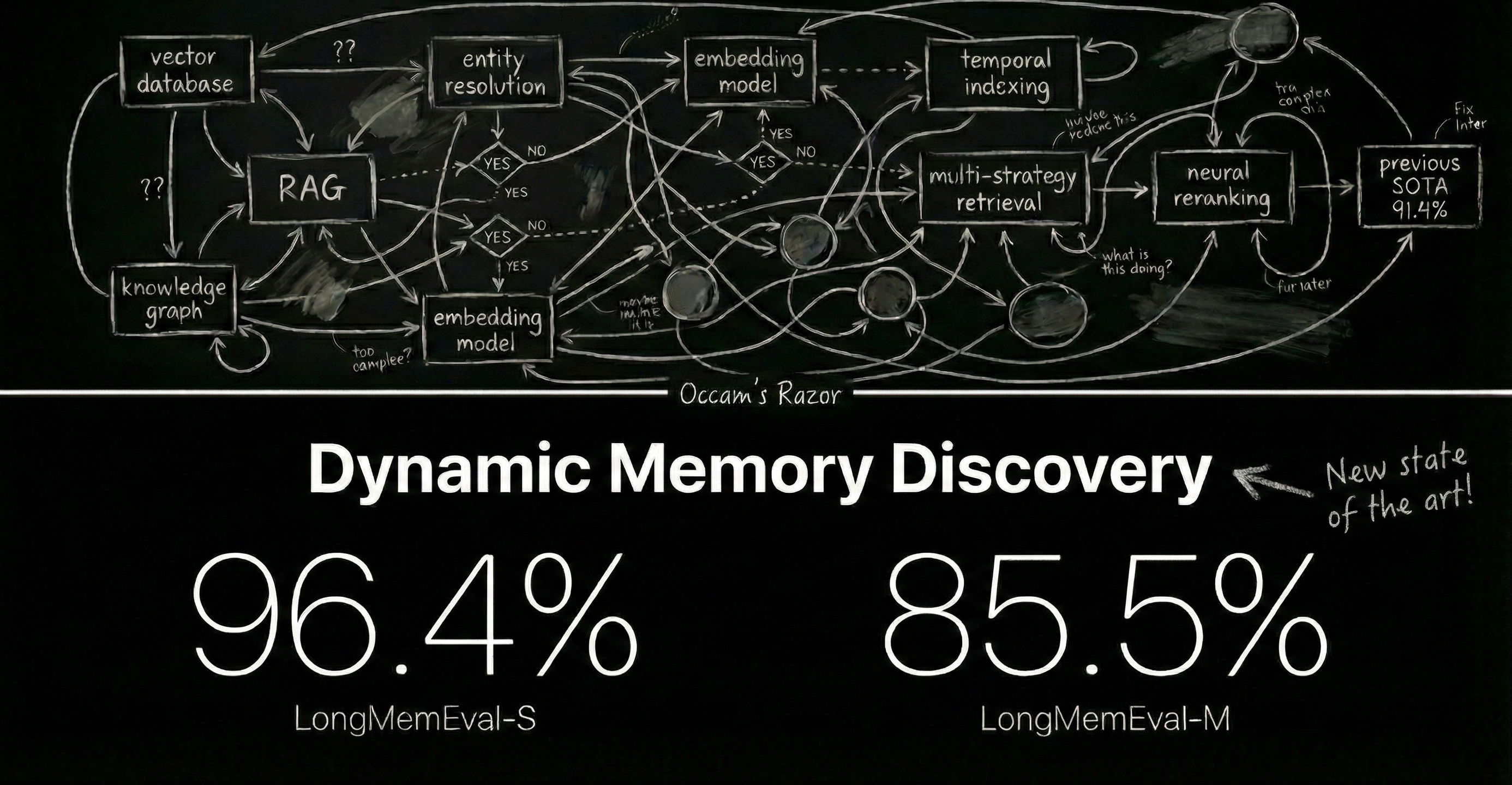

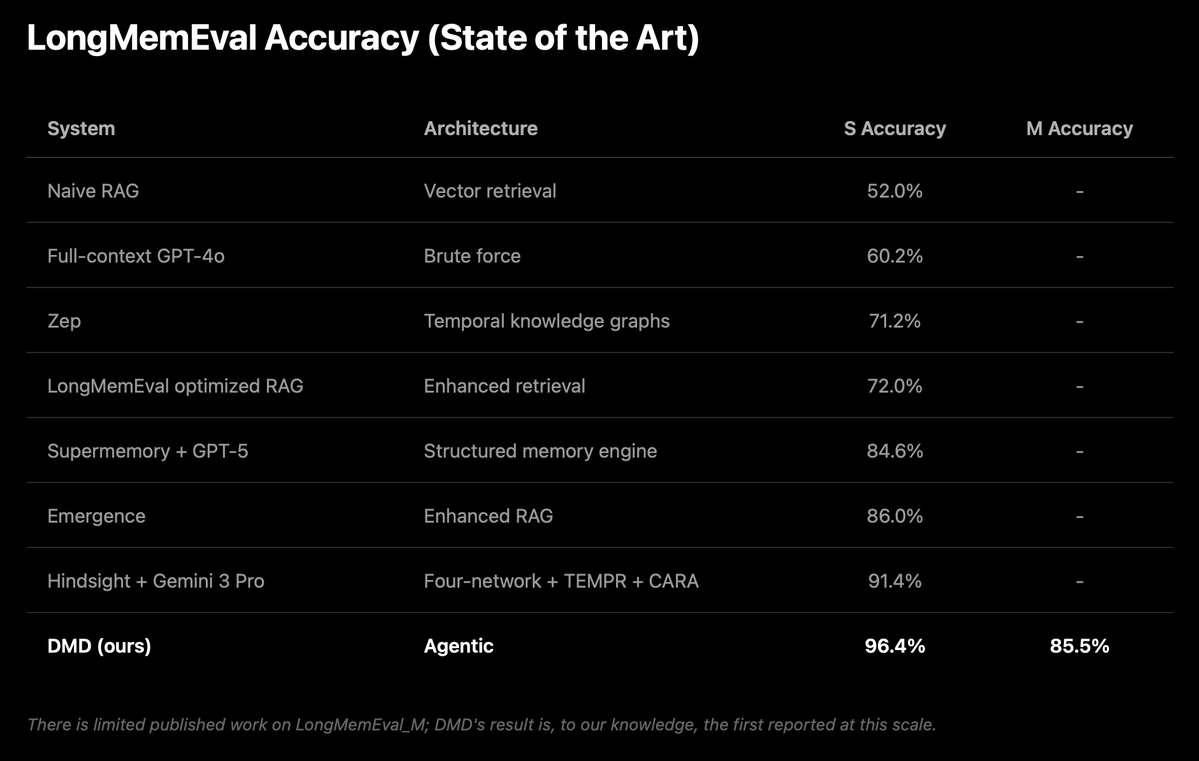

Dynamic Memory Discovery (DMD) achieves 96.4% on LongMemEval_S and 85.5% on LongMemEval_M, both new state of the art results.

This post is about why it works and what I think the field is getting wrong.

Against complexity

There is a pattern in engineering that repeats across decades and disciplines. A problem is declared hard. The field builds elaborate solutions. The solutions become the orthodoxy. Then someone tries the naive thing and it works better than all of them. Long-term memory for conversational AI has followed this pattern exactly. The field has been layering increasingly complex infrastructure to compensate for model limitations. Early systems relied on vector databases and knowledge graphs. More recent ones added multi-strategy retrieval with neural reranking, specialized networks for separating facts from opinions, and temporal reasoning agents. The previous state of the art, Hindsight, combined four separate networks with entity priming and adaptive reasoning. Each generation is more sophisticated than the last. Each built on the assumption that you need custom infrastructure between the model and the data.

I took a different approach.

Occam's Razor

Occam's Razor is often summarized as "the simplest explanation is usually correct." But the deeper principle is about assumptions. Every unnecessary assumption in a theory is a place where the theory can be wrong. The version with the fewest assumptions is preferred not because simplicity is aesthetically pleasing, but because each assumption is a bet, and the fewer bets you make, the fewer you can lose.

This applies directly to systems design. Every layer in a retrieval pipeline is an assumption about what the model cannot do on its own. DMD refuses to make these bets.

The result is a system with almost no assumptions to be wrong about.

And that, more than any clever engineering, is why it wins.

The proof

LongMemEval is the most widely used benchmark for long-term memory in conversational AI (ICLR 2025). 500 questions testing the things memory systems actually need to do: finding facts, reasoning across sessions, handling temporal logic, tracking updates, and knowing when to say "I don't know." It comes in two sizes. S requires searching through 115,000 tokens of context across 50 sessions per question, roughly one full-length novel. M is substantially larger: 1.5 million tokens across 500 sessions per question, roughly 8–10 novels stacked together. Most published work (as of February 3rd, 2026) has only tackled S.

As mentioned, DMD achieves 96.4% on S, surpassing the previous state of the art (Hindsight, 91.4%).

On M, it scores 85.5%, the first result I've seen reported at this scale. The same approach, without modification, shows a remarkable ability to handle a 13x increase in context with modest regression in performance.

The LongMemEval_S benchmark is effectively solved.

The remaining errors on S are largely questions of true ambiguity. Take Q150: "How many points do I need to earn to redeem a free skincare product at Sephora?" In the conversation history, the user said "I just hit 200 points and need 300 to redeem." DMD answered 300. The benchmark says 100. Does "need to earn" mean the total required, or how many more you still have to go? DMD read it one way, the benchmark read it the other. This is a judgment call, not a system failure.

Where intelligence should live

There is a useful analogy from the history of networks. In the 1990s, the telecom industry bet on "Intelligent Networks," architectures where the network itself was smart. It would route calls, manage quality of service, and handle complexity at the infrastructure layer. The internet took the opposite approach. TCP/IP is a dumb pipe. It moves packets. All the intelligence lives at the edges, in the applications, where it can evolve independently and improve without touching the underlying infrastructure. The dumb pipe won. It won so completely that the Intelligent Network is a historical footnote.

Memory pipelines are the intelligent network of AI. They push complexity into the infrastructure: embeddings, indexes, retrieval strategies, reranking models. All of it designed, maintained, and rebuilt every time the underlying models change.

DMD rejects this entirely. The infrastructure is in its simplest form, and it does nothing. The intelligence lives with the frontier models, which improve every several weeks.

Simplicity is not a limitation

Most memory frameworks build complexity to avoid spending intelligence on the problem directly. The assumption is that intelligence is expensive, so you engineer around it. Dynamic Memory Discovery pays the cost. A single question might be more expensive to answer, but DMD gets the answer right more often. It is not solving the cost problem. It is solving the one where accuracy matters more than anything else.

Yes, there are real use cases where cost and latency constraints make complex retrieval pipelines the right choice today.

But the word today is doing a lot of work in that sentence.

GPT-4 launched at $60 per million output tokens. Equivalent capability now costs under $1. That is a 98% collapse in two years. Stanford measured a 280x cost reduction between 2022 and 2024: a task that cost $1,000 in AI compute now costs $3.57. The price of intelligence is falling so fast that any system designed to avoid spending tokens is building around a constraint that is actively disappearing.

Inference speeds are collapsing at a similar pace: frontier models now routinely deliver 100–200+ tokens per second in real-world serving (with lightweight variants pushing 500–600+ t/s), compared to the ~20–50 t/s just 1 or 2 years ago: a 5–10x jump.

Every complex memory pipeline is a workaround. And workarounds become obsolete when the thing they're working around stops being a constraint.

As those limitations disappear, what will remain is what DMD already is: the simplest possible thing.